Master Storytelling With 4 Types of Narrative Writing

Narrative writing is storytelling, and storytelling is everywhere.

It’s in movies, books, podcasts, and even the ads you’re forced to watch all the way through before your ASMR video starts.

Humanity figured out long ago that nothing engages hearts and minds like a story. So, naturally, we use stories to convey just about everything.

We use them to entertain and inspire. We use them to deliver information, wrestle with complex ideas, spark empathy, and motivate others to take action.

But none of this happens by magic. It takes a little know-how and a lot of practice. Fortunately, you’ve come to the right place for the know-how.

You and I are going to dive into all the essential basics of narrative writing. We’ll explore the many places storytelling shows up across all genres of literature and discover the four main types of narrative writing.

We’ll also cover major topics like story structure, point of view, and advanced narrative technique.

First, the big question:

What is Narrative Writing?

A person makes a choice, and that choice causes something big to happen, which causes an even bigger thing to happen, which causes the biggest thing to happen…

…and that’s narrative writing in a nutshell.

A narrative is a story, and a story is a string of cause and effect driven by character choices. How you set up this domino chain depends on your genre, which we’ll explore more in a bit.

Characteristics of Narrative Writing

This type of writing generally falls under the category of creative writing. That means it’s written from a subjective perspective with the goal of discussing complex themes and/or evoking emotion.

To pull off such abstract feats, creative writers rely on descriptive language and literary devices like metaphors, symbols, and irony.

A narrative also incorporates key storytelling elements like these:

Setting - This is the world in which a narrative takes place, including both the physical surroundings and cultural context.

Plot - The plot is the chain of events that roll out as the story progresses.

Characters - These are all the beings (often human, but not always) who populate the story. Character decisions drive the plot forward, and it's also the characters who suffer or thrive as a result of the story’s events.

Characters are responsible for getting your readers emotionally engaged. If you write your characters well, your audience will care what happens to them.

Conflict - Most narratives contain several conflicts, big and small. A conflict arises any time an obstacle stands between a character and their goal. There’s always one primary conflict, and it’s between the main character (protagonist) and the character (antagonist) or situation that prevents them from reaching their objective.

Narrative Arc - This is the overall shape of the story. While the specifics can vary depending on which story structure you use, you’ll usually see the tension building as the conflict grows worse until the outcome is finally decided in the climactic scene. After that, everything chills out a bit.

The Narrative Genres

We tend to associate narrative writing primarily with fiction. But as I mentioned before, human beings have a habit of turning everything into a story.

So it likely won’t come as a surprise when I say you can find the narrative technique in nearly every corner of literature.

Here’s a quick rundown of the most story-centric genres:

Fiction Narratives

If it’s not true, it’s fiction. And most fiction is narrative.

But not all of it. Pawnee: The Greatest Town of America is a comical guide to a town that doesn’t exist and is “written” by Leslie Knope, the best person in the universe, who also doesn’t exist.

A lot of “not true” happening there, but it’s still not narrative.

Let’s talk about the fiction genres that do fit into the narrative category.

Forms and Genres

Narrative fiction includes things like:

- Novels

- Novellas

- Short stories

- Flash fiction

- Screenplays

- Teleplays

- Stage plays

- Narrative podcast and radio scripts

Fictional stories can be separated further into genres. The genre of a written work is defined by its tone, content, and style. The most common narrative genres in fiction include:

- Literary fiction

- Romance

- Fantasy

- Science Fiction

- Thrillers

- Horror

- Mystery

- Comedy

- Action-Adventure

- Historial Fiction

Nonfiction Narratives

Nonfiction is, of course, the opposite of fiction. The chain of events that occur in a work of narrative nonfiction are true.

People don’t often think of nonfiction when they think of narrative writing. We’re more inclined to view stories as something someone made up. After all, you have more control over them that way. You can manipulate them to fit a structure and highlight a theme.

Turns out, narrative nonfiction writers know how to do the same thing while staying true to the facts. And odds are, you’ve read this type of storytelling before.

Forms and Genres

Narrative nonfiction includes things like:

- Memoirs

- Autobiographies/biographies

- Narrative essays

- Journals and diaries

- Literary journalism

Standard news articles don’t fall under the category of narrative nonfiction, even if they guide the reader through a series of true events. It all comes back to the goal of the piece. A news article exists to inform the reader by presenting objective facts.

Narrative nonfiction, on the other hand, is deliberately subjective. The writer presents a specific perspective and uses descriptive language and literary devices to engage the reader’s emotions.

Narrative Poetry

Turns out, a poem can tell a story, too. Who knew?

You, probably. Even if you’re not a big poetry reader, odds are good that you encountered a narrative poem at some point in your education. Maybe something like “Annabel Lee,” The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, or “Casey at Bat.”

A narrative poem involves classic poetic devices like meter and (sometimes) rhyme, but instead of simply riffing on a theme, emotion, or moment in time, it tells a story.

Hybrid Narratives

Last but not least, we’ve got those tough-to-define hybrid narratives.

This includes stuff like faction, which is a portmanteau that I’d argue doesn’t really work because it’s already a word. But whatever, the term is out there and I must accept it.

Faction—both the literary term and the genre itself—is a blend of fact and fiction.

Then there are novels written entirely in verse, like Autobiography of Red and Inside Out & Back Again.

There are endless ways to mash up narrative genres and forms. As I said before, human beings will turn just about any style of communication into a storytelling opportunity.

But in order to do that well, they’ve got to know a thing or two about narrative technique. That brings us to…

4 Types of Narrative Writing

There are four common types of narrative, and you’ll see all of these types across all genres.

There are no rules about which narrative style you’re “supposed” to use. What matters is that you know why you’ve chosen a specific type. That is to say, you understand how that style influences your reader’s experience of that story.

Let’s break this down so you can make that decision with a little more clarity.

Linear Narrative

In a linear narrative, the author lays out the events of the story in chronological order.

The first stories we ever hear fall under this category. The Big Bad Wolf blows down the house of straw, then the house of sticks, and then fails to blow down the house of bricks.

A linear narrative is straightforward and allows the reader to experience the story the same way they experience life: one moment after another.

When you think about most of the stories you read, watch, and listen to, you’ll likely notice that most of them are linear narratives.

Nonlinear Narrative

A nonlinear narrative ditches chronological order. In this style of storytelling, the author might jump back and forth between timelines or incorporate chapter-long flashbacks.

It’s trickier to pull off a nonlinear narrative than a linear narrative. Readers can easily become disoriented.

So why do it?

Sometimes a nonlinear narrative can shed light on a character’s motivation by gradually revealing their backstory, like in Little Fires Everywhere. It might emphasize the expansiveness of the story’s theme, like in The Overstory, which spans a century’s worth of thematically connected plot lines.

A nonlinear narrative can also take the audience inside a character's fractured perspective, like in the movie Momento. On that note…

Viewpoint Narrative

A viewpoint narrative is a story that emphasizes the perspective of a specific character. Or characters if the author opts to tell the story through multiple points of view.

Now, to be clear, all great narratives have a point of view. What makes something a viewpoint narrative is how central the narrator’s perspective is to the reader’s experience of the story.

Gone Girl is a viewpoint narrative. The story is told from two different first-person perspectives with the goal of complicating the reader’s understanding of what’s real and who the true villain is.

Writers often use first-person narration or third-person limited point of view in this style of storytelling. You don’t have to, though. You could use third-person omniscient or even second-person narration if you wanted to. (More on all that in a bit.)

Just FYI, a viewpoint narrative can be linear or nonlinear.

Descriptive Narrative

If you’re writing a descriptive narrative, you’re more concerned with helping the reader experience the world of your story.

The Lord of the Rings is a descriptive narrative. Character perspectives matter, but what’s most important is that the reader feels enveloped in this world. There’s a lot of descriptive language and vivid details about the landscapes, cultures, magic, and beings that inhabit Middle-earth.

If your story is defined more by its world than the individual perspectives of your characters, then you might opt for a descriptive narrative.

This style works for both a linear narrative and a nonlinear one.

What is Narrative Structure?

No matter which narrative style you choose, you’ll want to think carefully about the way you structure your story.

Narrative structure refers to the way you lay out your story’s events. Seems simple enough, but believe me, there’s a lot more to consider here than whether or not you want your narrative to follow a linear timeline.

This storytelling tool has such a significant impact on the way readers experience a story that there are actually several different types of structures. In fact, most genres favor certain formats to deliver the exact emotional journey audiences expect.

But that’s advanced stuff. If you’re interested, you can learn more about story structures here. For now, we’ll stick with the fundamentals.

Story Structure Basics

While specific story beats vary from one type of narrative structure to another, the vast majority of stories follow this same basic layout:

Exposition - Here, you introduce your protagonist(s) and setting.

Inciting Incident - This is when something happens—big or small—that forces your main character to make a major decision that changes everything. That decision will involve pursuing a goal in the face of serious obstacles.

Rising Action - Now your protagonist is in it. They’re running into roadblocks and coming up against their greatest weaknesses as they chase down their goal. The situation is getting dicier and the stakes are getting higher.

Climax - Time for your main character to fight their final battle—the one that forces them to take a huge risk and call on hidden strengths. This story beat determines your narrative’s outcome.

Falling Action - Now, after all that drama, your characters and world must find their new equilibrium. Who have they become as a result of everything they just went through?

Resolution - In this narrative beat, you tie up all your loose ends, restate the theme, and leave the reader with a vision of what life will look like for your characters going forward.

Nailing the Narrative Perspective

As important as it is to figure out what happens in a narrative, it’s just as crucial to determine how you want to tell your story.

That is to say, what’s the narrative perspective?

You might choose to use a character (or characters) as a narrator, laying out the events from their point of view. Or you could opt for a nameless narrator who tells the tale in the third person. Even then, your phantom storyteller will have a voice, tone, and perspective.

This is creative writing after all. We’re all about subjectivity here.

So let’s go over some key considerations when it comes to determining who’s going to tell your story and how, starting with the narrative point of view.

Different Points of View

A narrative point of view (POV) can take many forms, including:

First-person narration - A first-person narrator tells the story using first-person pronouns like “I/me” and “we/us.” This usually means the narrator is an active participant in the story, though you will occasionally see a first-person narrative where the storyteller seems to act more as an observer.

If you’re writing a personal narrative like a memoir, personal essay, or autobiography, you’ll almost definitely use this POV. In all other forms of narrative writing, first-person is optional.

Third-person narration - This POV comes from an outsider who never discusses themselves and tells the story strictly with third-person pronouns like “she/her,” “they/them,” and “he/him.”

You can break this down further into third-person limited and third-person omniscient narration. In third-person limited, the narrator only knows what’s going on in one character’s head at a time. An omniscient narrator, on the other hand, can tell you what everyone is thinking at any given moment.

Second-person narration - Second-person POV is rare, but it’s out there. You’ll encounter it in Choose Your Own Adventure books and experimental narratives like Interior Chinatown.

This style involves the use of the second-person pronoun “you,” which is like grabbing the reader by the wrist and yanking them into the world rather than gently drawing them in. Sometimes, this works really well, like in the examples I mentioned above. But it can also be a risky move.

Knowing Your Narrator

No matter which point of view you use, you’ll want to nail down to details about your narrator:

Voice - This is their personality on the page, defined by diction, rhythm, and tone.

Tone - This is how they feel about the story they’re telling. Is it romantic? Eerie? Disdainful?

These two elements work together to create an engaging storyteller. You need them, even if your narrator has no name or personal story. If you’re not sure how to develop voice and tone, click on the terms above and you’ll find guidance for each one.

Advanced Storytelling Techniques

Before we part ways, I’d like to offer a few bonus tips for crafting a narrative your readers won’t stop talking about.

Laying out a chain of intriguing events is a solid skill on its own. But if you want to get your audience nibbling their nails at the breakfast table, swooning at the laundromat, or staying up way past their bedtime, try enhancing your storytelling with one or two of these tricks:

Foreshadowing

Foreshadowing is a sneaky little maneuver where you keep your reader engaged and guessing by hinting at things to come. Usually bad things.

Your hints can be subtle and symbolic, like showing your protagonist struggling to parallel park in a space that’s too small as they arrive for a date with someone they’ll ultimately try to force themselves to fall in love with.

Foreshadowing can also be direct, like actually saying, “Clive miraculously secured the Taylor Swift tickets, but he wouldn’t live long enough to go.”

Flashback

A flashback is when you show your reader a scene that happened before the current timeline of the story. It’s a blast from the past, if you will.

Instead of just dumping backstory on them, you transport them to a moment that clarifies present events. You can use this narrative technique to reveal hidden information or help your audience empathize with a character’s fears or desires.

That said, this device can also interrupt the narrative flow, so make sure you read up on flashbacks before you go stuffing them into your novel.

Parallel Storylines

You may have read a book or watched a movie with two or more storylines that all seemed equally important but barely intersected with one another, if they intersected at all.

Those are known as parallel storylines. Writers sometimes use them to examine a theme in multiple contexts, show how the same event affects people differently, or explore similar experiences across generations within a single family.

If you use parallel storylines, it will be a defining feature of your book. So make sure that’s what you want before you have at it.

The Unreliable Narrator

Honestly, almost all narrators are at least a little bit unreliable.

Remember how we talked about the importance of narrative voice and tone even with a third-person narrator? Well, those qualities indicate perspective which indicates bias which means no story can ever truly be objective.

Even so, there is such thing as a blatantly unreliable narrator. They might be known con artists or love to embellish or be a little disconnected from reality. That kind of storyteller can really keep your audience guessing.

You can learn more about this kind of narration here.

Master Narrative Writing With Dabble

Now, here’s the crazy thing:

We’ve barely even scratched the surface of this narrative writing stuff. There’s so much more to explore, and you can find loads of insight for free in DabbleU.

And once you’re ready to start writing your own tale—whether it’s fact, fiction, or (sigh) faction—you can count on Dabble to keep you organized.

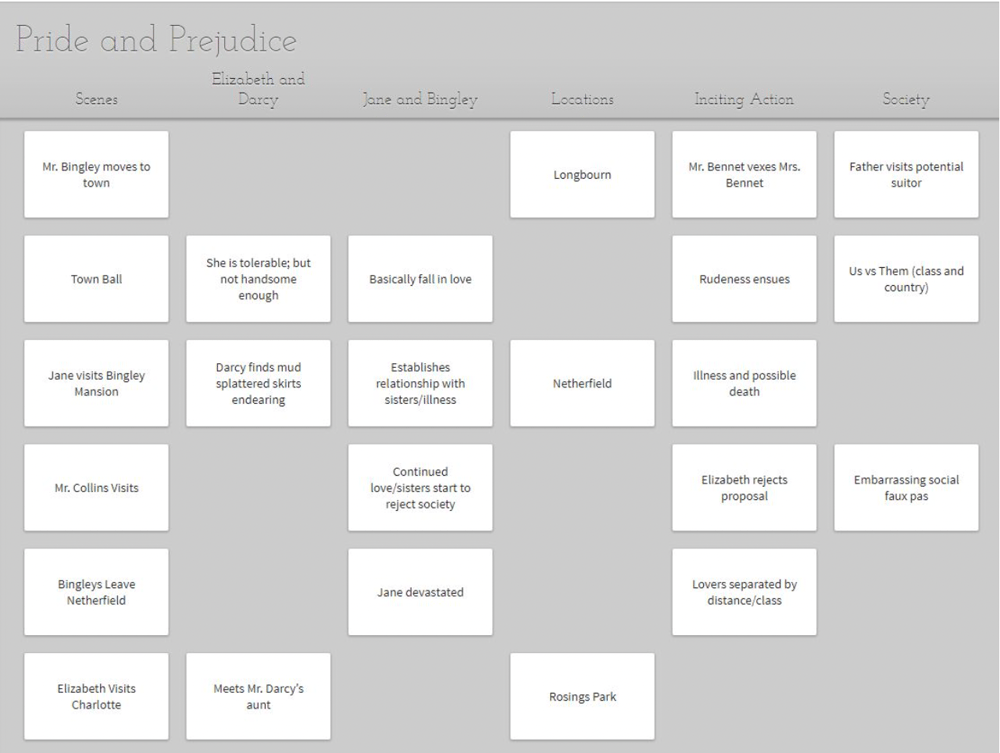

If you’re not familiar, this is an all-in-one writing tool that covers every part of the writing process. That includes a super handy Plot Grid for organizing all your narrative elements.

You can customize the Grid to meet all your needs and enjoy having your scene cards right at your fingertips as you draft your story.

Bonus: a Premium subscription also gets you access to live online writing workshops, deep dive newsletters, and a ton of other resources to help you hone those narrative skills.

Not a Dabbler yet? No problem. Click here to snag a 14-day free trial, no credit card required.

.jpeg)